4 STEPS TOWARDS SIMPLIFYING LAND USE REGULATION

What is Zoning and why does it exist?

In the most basic terms, privately held real property (land and buildings) and its use is regulated by local municipal authorities in order to preserve its value and benefit. By restricting potentially incompatible adjacent or nearby uses, zoning identifies the best use of land. Zoning regulations were initially adopted in the early part of the twentieth century, evolving in recent decades to become more form-based and shaping planning and land use at a broader regional level. In short, these regulations are typically issued by ordinance to classify and guide the development (or redevelopment) of pieces of property within a precinct.

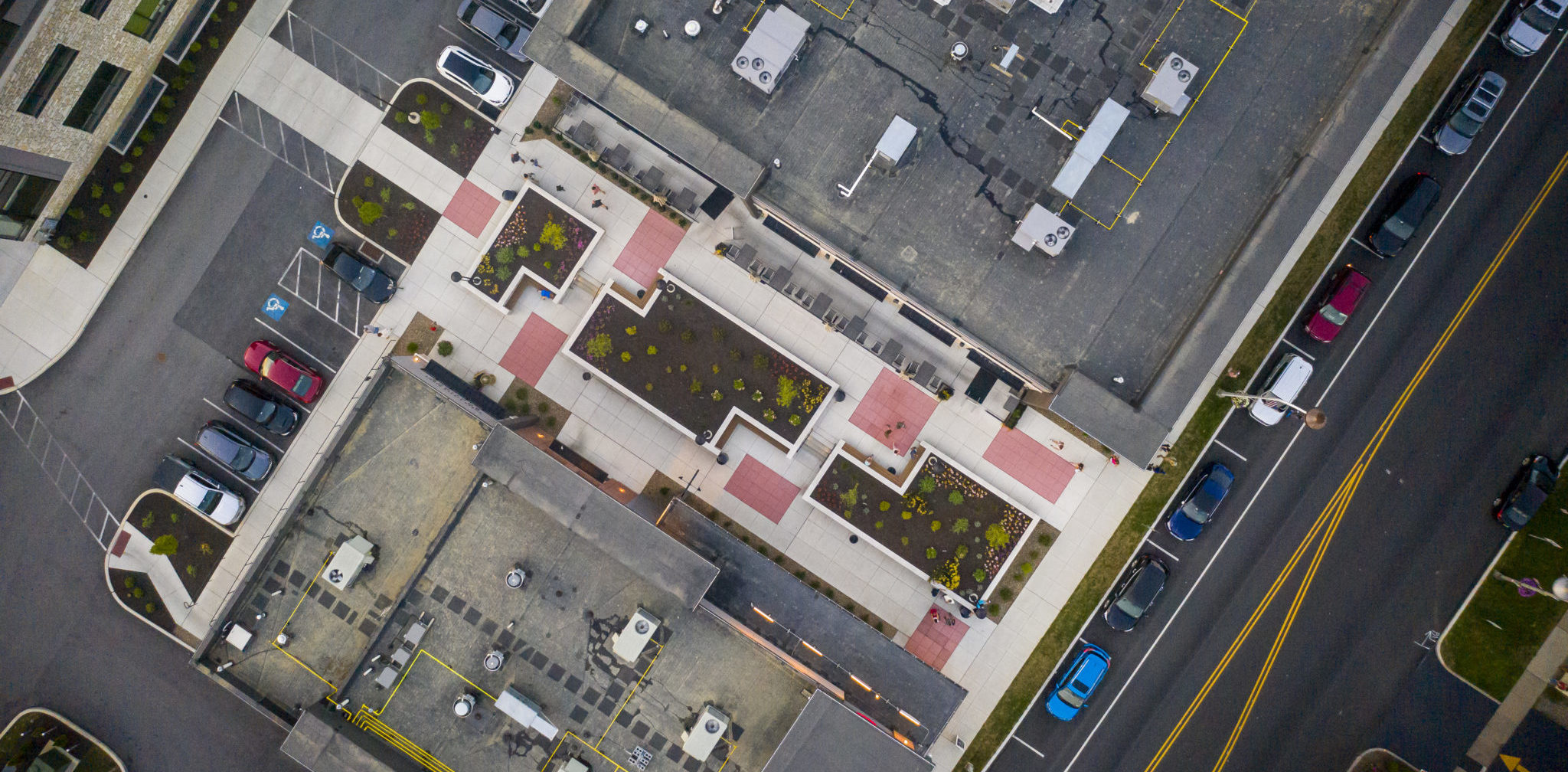

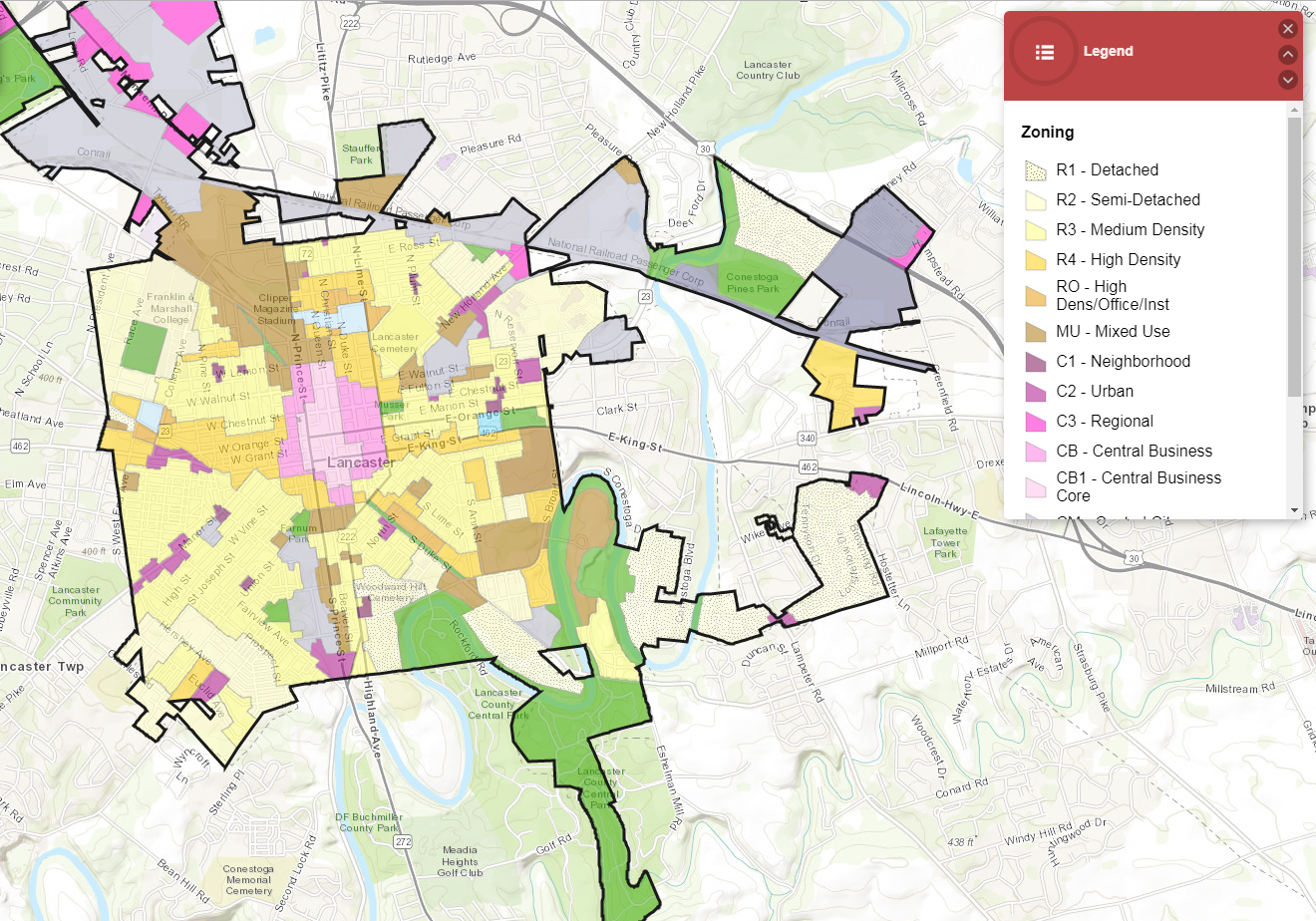

City of Lancaster Zoning Map

Sounds straightforward right?

Not so fast.

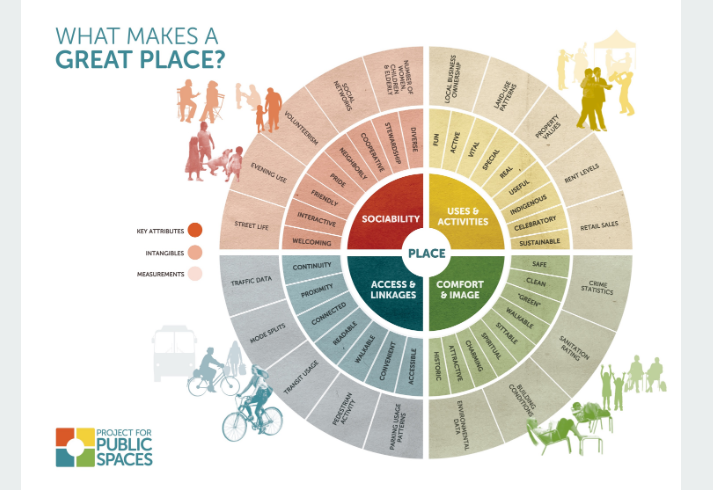

Strategies for successful place-making are inherently complex and rarely fit into convenient functional definitions, density requirements, or parking regulations—planning for the health and welfare of communities is not simple. There are the obvious situations whereby it is best practice not to locate petrochemical plants next to early childhood development centers; however, the fabric of our building landscape is interwoven with layers of backstory, political decision-making, and economic policy.

In other words, static ordinances based upon principles inherited from a century ago are becoming less applicable now in a time when resources are more precious, uses are more mixed, and our collective expectations have changed regarding the quality of rural, suburban, and urban settings.

What Makes a Great Place? Diagram provided by the Project for Public Spaces

What are the big challenges?

1. The permitting process is slow and burdensome

Most land use regulation and permitting occurs at the local level, although resource conversation (including the management of rain and ground water) typically occurs at the state level. With numerous agencies requiring independent, but related approvals, rarely do the schedules of these governing bodies conveniently align to provide a straightforward, step-by-step process. Moreover, meeting and approval cycles tend to be drawn out into monthly intervals, prolonging submission reviews and hearings.

2. There are competing interests (historic, rain water management, development initiatives, resource conservation, etc.)

Departmental oversight of land use occurs at various levels of government. Each maintains their own objectives and interests, which sometimes compete, leading to compromise and confusion. For example, when considering property improvements or the removal of features, older urban centers often contain historic overlay districts with specific guidelines and review processes. Meanwhile, redevelopment incentives might promote progressive approaches towards energy conservation, greenspace, or diversity of uses, running counter to the historic preservation strategy for a locale.

3. Regulators are not always well-informed

With most land use regulation enforced at the local level, the facilitators of the approval processes are often community activists and volunteers. Zoning hearing boards, historic architectural review boards, appeals committees and the like are mostly populated by non-professionals who, although well-meaning and committed to their service, are not necessarily educated in the particular fields of interest or able to invest the concentrated involvement needed to move approvals along in timely fashion.

4. The rules are antiquated

With most modern land use policy spawned from mid-twentieth century context, many rural and suburban ordinances remain provincial and outdated. Density is typically shunned and pedestrian-friendly or multi-modal planning strategies give way to zoning and planning for the automobile. The laws surrounding parcel management remain rooted in protecting individual and often incongruous pre-existing land functions at unreasonably low densities.

TONO Group owner, Hunter Johnson, AIA, attends a focus group of Lancaster’s leading land use and design firms to discuss challenges and solutions surrounding the county’s zoning regulations. The discussion was part of the Lancaster County Planning Commission’s comprehensive plan for the future, Places 2040.

So, what’s the solution?

Sustainable land use practices require strategic and proactive forethought at inter-municipal levels, particularly when considering the stewardship of diminishing natural resources and the complexities of thoughtful place-making.

1. Streamline the process

Remove barriers to successful planning by reducing the number of regulatory bodies having jurisdiction over the process in the first place. Land use strategies should occur at a more regional level, allowing for consistency of application and fewer competing interests. Moreover, centralized decision-making affords less need for the proliferation of volunteers, localized boards, and committees.

2. Prioritize interests

With consolidated agencies and a more regionally proactive planning approach, otherwise competing interests can be mitigated. At a fundamental level, planning must be regional and purposefully comprehensive, whereby the stewardship of natural and cultural resources take priority. From there, infrastructure networks for transportation, utilities, and public services should be thoughtfully prioritized before giving way to individual and piecemeal parcel-by-parcel decision-making.

3. Educate and empower decision-makers

Given the sheer quantity of approval agencies at the municipal level, it’s easy to understand why many are composed of non-professional volunteers only able to invest a few hours a month to serve their cause. Consolidation will help reduce competing interests and streamline processes; however, more so, directly applicable and professional training will better empower these decision-makers to build stronger, more vital communities. Certainly municipal, county, and state professional engineering and planning staff members shoulder the responsibility to implement policy, but the governing bodies are frequently populated by laypersons requiring guidance and careful management by the paid professionals.

4. Get with the times

As populations grow and shift, new technologies shape transportation methods, resources become more valued, and the expectations for quality of life increase, so too our planning policies must evolve. Gone are the days of highly localized, neatly uniformed prescriptive zoning ordinances that keep within the confines of otherwise artificial political boundaries. Today, our communities demand bigger thinking to solve bigger issues. The ultimate goal is to remove impediments to creative problem solving.

How Zoning Laws Are Holding Back America’s Cities, courtesy of The Institute of Humane Studies

To place the discussion into the broader context and help define successful planning, particularly when examining the urban context, one must inherently defer to Jane Jacobs and her paramount work of 1961 The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Jacobs writes that cities possess “a most intricate and close-grained diversity of uses that give each other constant mutual support, both economically and socially”. Furthermore, she states, “dull, inert cities, it is true, do contain the seeds of their own destruction and little else. But lively, diverse, intense cities contain the seeds of their own regeneration, with energy enough to carry over for problems and needs outside themselves.”

Future land use regulations must be streamlined, informed, and allow for diversity and flexibility of use. This will encourage communities to evolve according to the needs of those who inhabit them.